Twaabane Creative Centre

Vocational Skills Training Centre

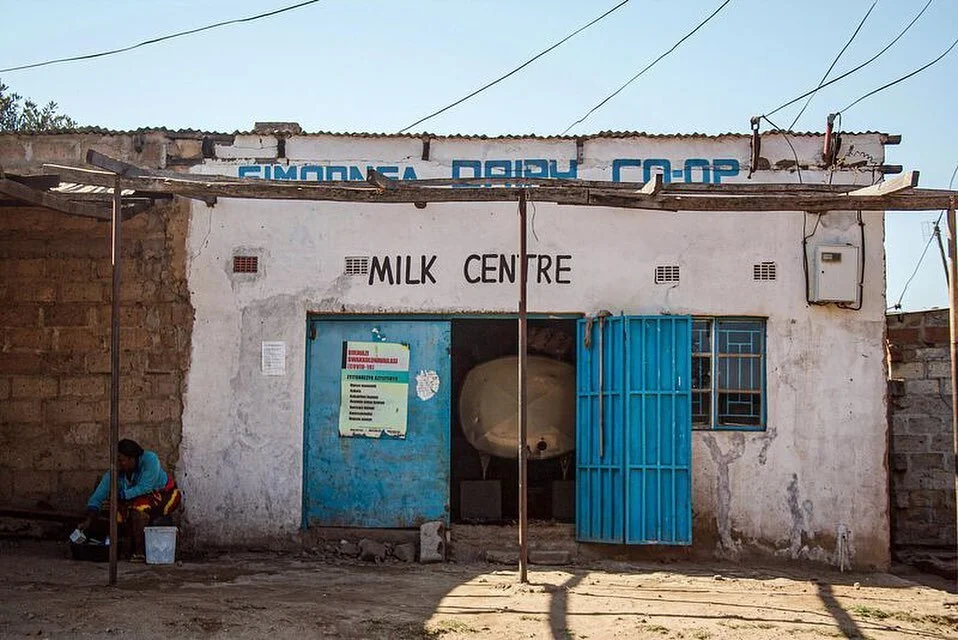

Simonga, Zambia

Twaabane Creative Centre is a vocational skills training centre in Simonga, Zambia. We deliver high-quality vocational training to members of the surrounding community, providing new skills and economic empowerment.

In the local Chitonga language, ‘Twaabane’ translates as “Let us share”. The word stems from the spirit of Ubuntu, which is a Bantu word for oneness and sharing ideas, skills and values to uplift a community.

In Simonga and Sinde villages, a Livelihood Survey (ByLifeConnected, 2021) revealed that the average employment rate for women was 36 per cent, compared to 58 per cent for men. In addition, employment was inconsistent and included casual work on farms, in local market stalls, or running personal businesses. This is underpinned by two key issues:

Low educational attainment and literacy levels -most of the women who were interviewed had dropped out of school in 7th grade (at age 13)

Lack of access to skilled vocational employment pathways –the closest training centre is 18 km away

Provincially, there is low uptake of vocational trade courses. Only 18 per cent of vocational examinations taken in the Southern province were associated with a trade. Additionally, many of the highly-skilled artisans and artisan companies are found in Lusaka. This has resulted in a skills gap and created high demand for qualified trades people and artisans in the Southern province.

The artisanal sector has the potential to make a powerful impact on the livelihoods of many Zambians, yet it is currently under-utilized. With the increasing demand for ethically sourced and handmade products, this sector is in a unique position to become a serious global player. The purpose of Twaabane is to contribute toward this demand and promote social and economic development in Simonga by improving access to income generating opportunities and education. Twaabane Creative Centre does this through the provision offree, high quality skills training,vocational employment pathways in the artisan sector, and access to adult literacy classes

An audio recording of the Twaabane Women singing a song in ciTonga entitled ‘Tweendela Luyando” which translates as we walk in love.

My journey with Twaabane

In June 2022, I took on the role of the Creative Project Lead at the Twaabane Creative Centre which had been officially been opened three years prior in 2019. The following year the COVID pandemic swept across the world devastating many communities. Simonga was of no exception. As an extension of Livingstone, which lies in the edge of the Mosi-oa Tunya National Park, the land around and of Simonga is mostly farms and lodges. These farms and lodges provide for the majority of employment opportunities for the people of Simonga. When the pandemic asphyxiated the systems of movement across borders, the flow of tourism and agricultural produce came to a slow rumble and in many cases a sharp halt. This directly impacted the employment rates of residents in Simonga. In the case of the Twaabane Creative Centre which is in the heart of Simonga, the newly established flow begun to churn slowly, adhering to the global crises.

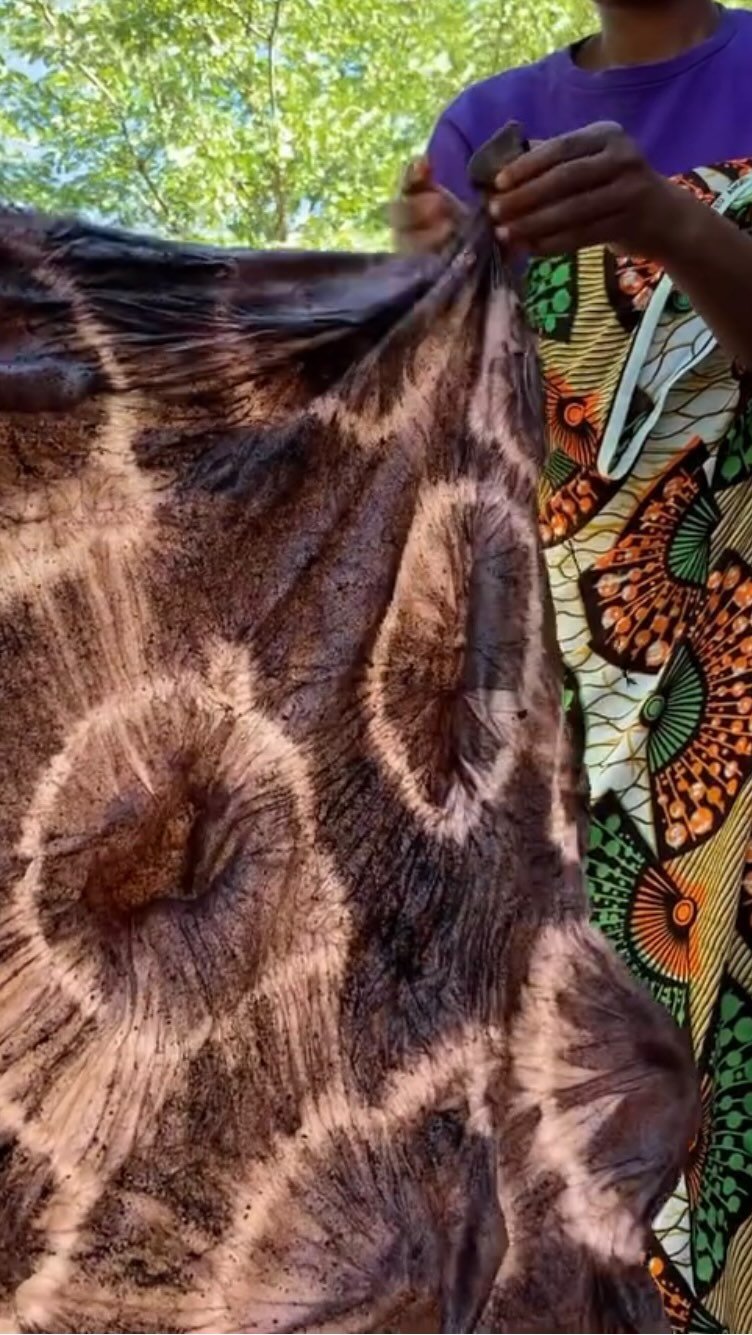

By the time I arrived at Twaabane, a team of 7 women, Bridget, Anna, Ferry, Josephine A, Josephine M, Regina and Charity had undergone a tailoring training designed to introduce them to foundational and intermediate textile skills. The women knew their craft. In the Textile Studio was the humming of the old singer machines and the vibrant chatter of the undulating ciTonga and ciLozi languages. Soon after another group from Simonga and Sinde were recruited to undertake the training programme. During that time my contract included developing a product or series of products which the women would make and put out into the local and national artisanal markets as a means of generating income and the fostering self-sustainability of the centre. It was in this capacity that the Natural Dye Project and the range of ethically tailored products of the Twaabane Creative Centre were birthed.

The first stage of the shift included teaching and implementing and in many cases resurfacing a series of design principles, and thus products, rooted in both indigenous knowledge and climate mitigation solutions. One of the first products of this kind was the ‘Scrappy Tote’, a tote bag which was sewn or quilted together using offcut or waste fabric from projects in the past. These totes make use of fabric which would otherwise have eventually landed up back in nature. Looping themselves around the branches of the Mopane Trees or around the dainty legs of the Fork Tailed Drongo. The quilting technique also carries and tells the story of the many fabrics, and in many ways stories of people, which passed through the hands of the women, and through the little magical space between the feed dog and the base of the machine. The second was a wide brimmed sunhat which was made using excess shade cloth, a lightweight netting made from low-density polyethylene and designed to block a certain amount of sunlight. The fabric was used a few years prior to create a shelter or cover of the ampitheatre at the Tongabezi Trust School and was sitting in the fabric store room. Michael, the assistant trainer and a few of the first team of 7 had experimented with creating a series of products from this material such as purses but these found themselves in the storeroom under stacked metres of chitenge fabric. The sunhat design emerged as a response to not only the excess fabric but to the sweltering hot sun of the Zambezi Valley. The third was the revival of a design of a half-cap which made use of discarded 5l oil containers as the material which formed the protective shade element of the hat.

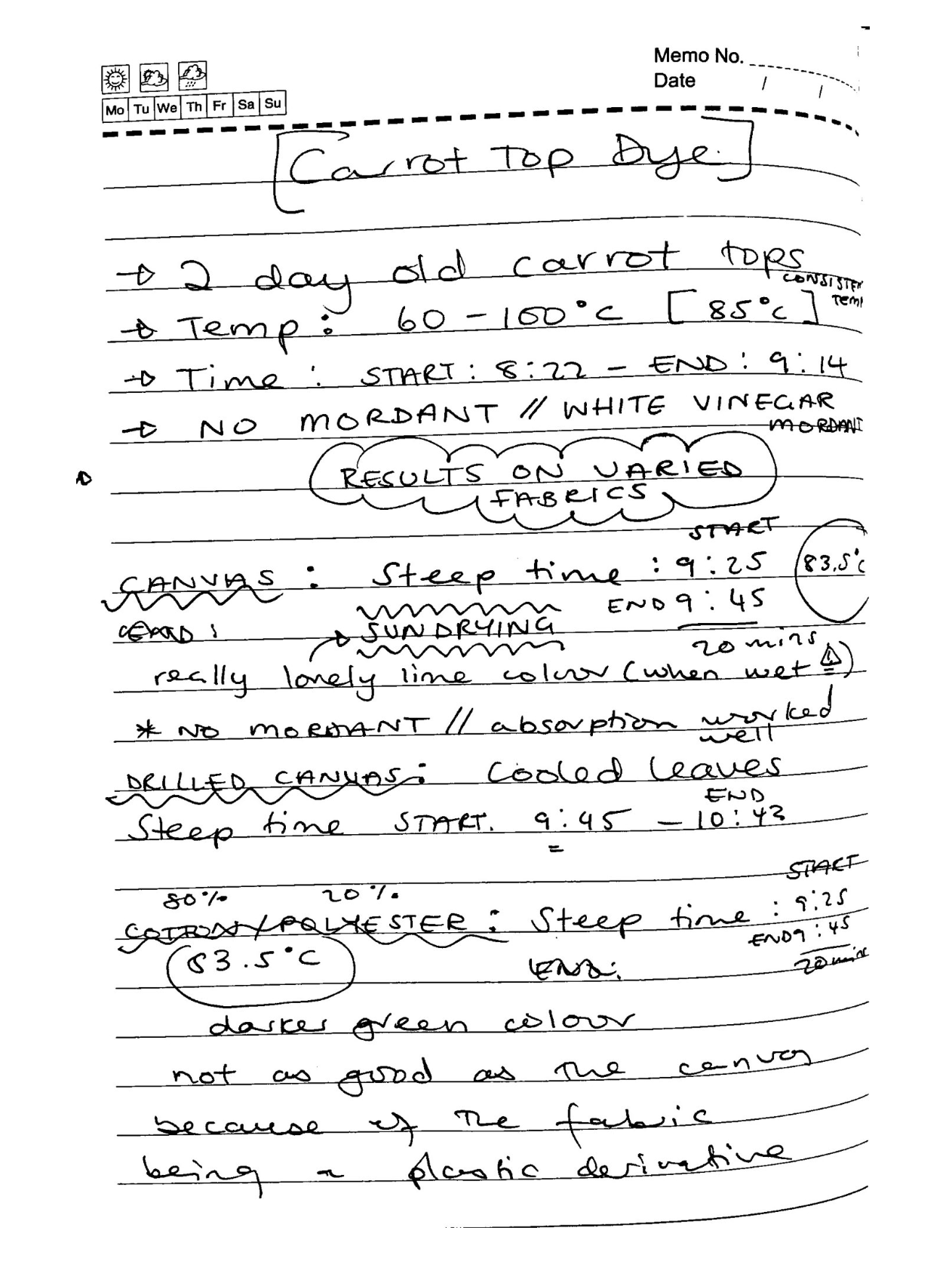

Alongside this, I was conducting research and experiments in my kitchen and around the Mopane and Miombo Woodland in search of natural non-toxic dyes which could be found and synthesised in the Zambezi Valley. The research project was sparked by a need to develop a flagship textile product, which indeed was able to generate income and support the self-sustainability of the centre but one which was was “crafted with passion and purpose for people and the planet.” a slogan I had developed for a range of artistic and artisanal products. This is now the main motto of the Twaabane Creative Centre. The initial testing stages made use of agricultural offcuts (or waste) from the Bulimi Garden, a project running alongside the Textile Studio. The first test was conducted using carrot tops, as the women in the garden had harvested a crate of organically grown vegetables and amongst them were carrots. The goal was to nurture a cycle of interconnectedness between the two skills development projects running under the Centre. The pigment extraction and process done using the Bulimi carrot tops yielded a pale yellow/green pigment.

The second tests were conducted using wild or foraged botanicals found around the Mopane and Southern Miombo Woodlands, such as musekeseke, sickle bush pods, mopane and munzinzila bark. The goal was to reconnect the stories and fibres between the indigenous knowledge of plants and their aesthetic textile properties, such as their ability to dye, found around Simonga and amongst the Lozi, Tonga and Tokaleya communities. This is how the almost two year old project begun.

Natural Dye Project

designed for the Twaabane Creative Centre through trial and error, intuitive listening and the guidance of indigenous knowledge of the land tucked into the pockets of Simonga and Sinde

A sample of colours which have been yielded using Musekese, Rooibos, Munzinzila, Avocado Pits and Muzauli

In February 2024, one year and nine months into developing and refining the Natural Dye Project for the Twaabane Creative Centre, my role at the centre morphed in shape. I went from occupying the role of the researcher and occasional teacher to being a Trainer. In this new phase, four women, Bridget, Chuma, Yvonne and Ferry are being undergoing a three month training programme Natural Dyeing. The programme is constitutive of elements of sustainable foraging and climate education.

The programme is taught in mainly ciTonga with translations available in ciLozi. A majority of the resources and case studies used in the curriculum have been selected based on their applicability and accesibility to the women of Twaabane. This means local sources in local languages are prioritised, these are often people within the community who are valuable in the teaching and learning processes. These local knowledge systems are contextualised in the global world through sharing media such as videos and images which can provide understanding beyond the comprehension of language but through imagery and non-verbal storytelling.

Although this may be, the women are encouraged to engage with the English language in certain scenarios which may yield their benefit but not at the detriment of their mother tongues.

As indicated above, one of the trees found in Simonga which yield a substantive dye is Muzauli (Pterocarpus Tinctoria) a tree which is currently being heavily exploited and exported. One of our lesson was entitled Muzauli How to work with an endangered tree + Discussion on deforestation and climate action solutions.

Muzuali (Lozi), Mukula (Bemba) Rosewood (English), Pterocarpus Tinctoria (Latin)

During the discussion a few point were mulled on such as its uses in the local and global contexts. “This tree is used for furniture, stomach aches and the fruit/seeds are used as a food additive., similar to pounded nuts or mongongo. Due to mainly timber logging, the mukula or muzauli tree is one of the most overharvested indigenous trees of the country. The mukula industry is worth an estimated 9 billion USD! “

Within this context Bridget shared that she has first hand experienced and been exploited by the timber logging industry. Timber companies or individuals would offer local people between 50-100 ZMW to chop down large trees. She shared that these trees were and are significant to the community as they provide food sources in times of crop failure. She also shared that there are a number of timber logging training sessions for rural people.

Based on this discussion it was agreed that we would take extra precautionary measures when using Muzuali as a dye. “This includes the ban of harvesting directly from the tree. What we can do is:

Forage off the floor around the tree as it sheds naturally

Contact carpenters for their offcuts.”

Bridget watching a video on indigenous dyeing practices in The Gambia during a lesson on alternative extraction techniques

Ferry straining the dye yielded from Munzinzila, a pigment used by the Lozi and Tonga basket weavers.

The team are showing incredible dedication and openness in accepting and fully taking ownership of the Natural Dye Project and its mission of Reindigenisation. During a Women’s Day Celebration in Livingstone in March 2024, Chuma presented the project to the President of Zambia who was highly supportive of the initiative. He purchased products and invited the ladies to exhibit at the Nature Based Solutions Conference held a few days later. This is only the beginning.