About Archive

As a community of practitioners collaborating across regions and socio-political environments, at the core of our work lies a commitment to disrupt Eurocentric epistemologies. As a result, our work is deeply rooted in a sustained scrutiny of the role of languages, visuality, and archives in the perpetration of the coloniality of knowledge.

Our impulse to publish stems from the desire to disseminate stories for the subversive potential they can yield, creating cracks in dominant narratives, fleeing accounts of history with a capital H and turning to the power of the fragment. We conceive archives as sites, institutions, repositories of knowledge/power, systems of thought and violence, but also as counter-practices of collecting, preserving, disseminating and organizing experiences of resistance.

Through a publishing practice grounded in collective, transdisciplinary and cross-cultural collaborations, Archive is invested in un-weaving repressive narratives and reclaiming the archive itself as a tool which no longer categorizes but rather continuously un-fixes, de-archives and re-archives through non-hegemonic models.

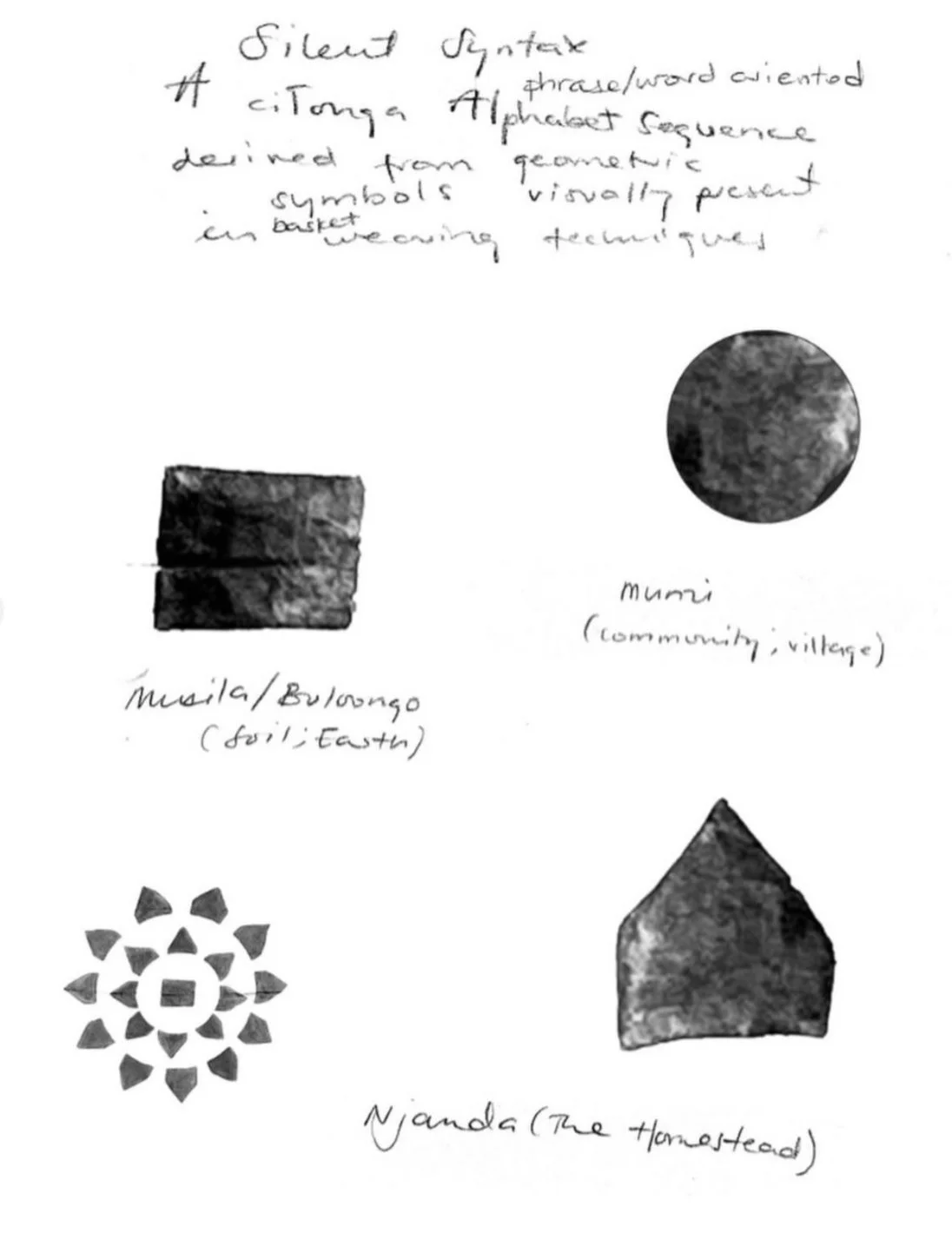

In response to the invitation from Archive Ensemble and the context of the Dak’art 2024 Biennale theme, The Wake, I proposed an experimental iteration of Silent Syntax: Tonga Basketry and Geometric Language Study. The project began in May in 2023.

I have been surrounded by these intricate expressions of the relationship of my ancestral mothers and the earth from time in memorium. My grandfather who was born in Nampeyo in 1935 maintained his connection with his home and made sure that his children and grandchildren did the same. It was on this note that traces of his ancestral home filled our home in Lusaka. A number of the baskets I own today have been inherited from the collection of my family home.

It wasn’t until I was much older that I began to connect to and with these telluric offerings having found or nurtured a deep connection I always had to the earth. I began to see baskets as vital parts of a counter archive on which stories of baTonga women were recorded. This was for me the arrival at a point I was able to use the baskets as a way to challenge the authoritative nature of paper and writing as the western archive dictates is of the highest importance.

It was here that Silent Syntax came to life. It began as the process of reimagining the images and motifs present in baTonga basket weaving techniques. This was done as a way to (re)code and (re)create storylines woven into and told by the baskets of baTonga women. Symbols found in the baskets were extracted from the pattern and coded with a word or concept. It was an experimental reworking of stories inscribed in patterns and of a language embedded in fractals. The first experiments were conducted using homemade Mushroom ink from the common inkcap (Coprinopsis atramentaria). A pattern guided by the first sample basket in figure 1. was drawn and painted onto on canvas

fig 1. njanda pattern from personal collection

The second basket which inspired recoding and language development was fig. 2 a pattern that baTonga of theValley call iguwo, the wind. From this pattern, a letter or symbol in the silent syntax was derived. The symbol has been coded Musampizya, a word which refers to an aromatic herb that baTonga used in various expressions, from portals of spirituality to medicinal remedies.

Musampizya represents the relationship baTonga have with plants as a way to challenge the field of ethnobotany and how it often sees past the very same people it seeks to put into socio-scientific context.

Musampizya was first painted onto paper using a paint alchemised from stale coffee grown in Lusaka. The symbol is used as a base in creating a series of images, mostly of plants of significance to myself and to baTonga as a whole.

figure 2, iguwo, from personal collection

I was thinking about how in many cases words that exist in English often cannot be translated into ciTonga and the concepts or trajectories those words were given to similarly don’t translate into ciTonga or the way of life of the baTonga. Ethnobotany was one of the words I was evaluating using this framework. Ethnobotany is the name given to the study of the relationship between plants and people and would therefore be insufficient in encapsulating what IS the relationship between people and plants and opposed to its study. That’s where this letter/pictograph called musampizya has its root. In written (in the Latin alphabet) and oral ciTonga this word translates a specific type of shrub used to cleanse spaces and people. A morphed version of this word in ciTonga musampwisa is also used to refer to the epaltes alata flower which was used medicinally. Another morphed word is musampwizia which refers to the same plant but in the context of ritual mourning. It represents the symbolic non verbal or non academicised expression of the symbiosis between us (as baTonga) and the earth/natural environment/plant ecologies.

I’ve been experimenting with clustering or layering a singular shape, letter. meaning to create anew and the possibilities are endless.

untitled series of images (1-3) from musampizya reimagination and abstraction as play

Bird of Paradise

Musampizya botanical play

The bird of paradise was my grandmothers favourite flower and so one I hold foldy in memory and now in practice.