Healing The Damned

Project Background

Kariba: Healing the Dam(ned)

The story of the Kariba (Kaliba meaning ‘trap’ in ciTonga) cannot be told without acknowledging and amplifying the voices of those, in spirit or living, in bone or in root, who suffer(ed) the violent atrocities of conquest.

Healing the Dam(ned) is a project that begun in the latter part of 2023. It seeks to explore the impact that the Kariba Dam, an immense infrastructural scar of the colonial era, has had on the Indigenous baTonga and White Settler communities in the middle-Zambezi Valley. This work will investigate how the language of conservation and ecology is inextricably linked to colonial projects thus negating indigenous laws of environmental preservation. It will additionally explore the sociocultural fractures initiated by the separation of the Batonga across present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Between 1956-1959, an estimated 110,000 baTonga who lived on the banks of the Zambezi were displaced, rather than resettled as hegemonic literature reads. Made into environmental refugees and forced to migrate to lands that limited access to their local livelihood systems and resource bases. Kariba interrupted and reconstructed an entire identity of a people stripping them of their connection to ancestral rites, such as custodianship of the natural world.

Part of this intervention will be concerned with challenging the positionality of indigenous knowledge and belief systems of the Batonga. Situated within the layered conversations around environmentalism and climate change present in the post-colonial imagination. The occidental arcs of history and plateaus of the present have sidelined the Batonga systems of belief and practice as being valuable solutions to an alarmingly deteriorating environment. Employing critical focus from this perspective opens up the possibility of alternative approaches to healing the wounds of loss and damage by engaging in restorative practices in which the Batonga are central. An analysis of the change in various cultural expressions on either side of the Dam will be explored. Language, aesthetic expression, such as body modifications and basketry, and gender roles within frameworks of ecological/spiritual beliefs.

A second part will seek to highlight that the praxis of colonialism took on a new life after the construction of the dam. With its construction finally the white man had conquered an insofar unconquerable territory. In doing so, this facilitated a change in language, style and in the nature of colonial control. White settlers finally arrived in this area, creating what historian Dane Kennedy has called ‘Islands of White.’ These were isolated communities far removed from everything around them. The white community became one who cared about the environment, cared about the animals that lived here and wanted to protect them from the ‘other’ whom they never cared to understand in the first place. Prior to this, as has been long documented white settler communities in Africa believed their environment to be inhospitable and treated their ‘conquered neighbours’ as entities to be feared.

The breadth of this research will be conducted through the use of a range of research methodologies, like oral interviews, focus groups, case studies, the analysis of mixed-media and archival sources.

since then, the project has morphed into various artistic and research products such as images, poems, sound pieces and short films such as Musampizya and Reindigenizing Future Food. Within the context of these projects, Artificial Intelligence, has been (re)coded as Ancestral Intelligence using the frameworks of Radical Zambezian Reimaginings. A methodology which accepts and prioritises fictive realities as being a necessary component in the healing of critical gaps in history, especially those of marginalised and silenced people and communities. Ancestral Intelligence (AI) is the tool first used in the development of Musampizya, a series of images which have been generated in the absence of images (free of colonial violence) of baTonga at the site of the dam, and in the surrounding forests and plains before it was built. The series of rendered self-portraits, uses digital technology to challenge the way in which the history of places like Zambia, have been told by Western Historians and Researchers using conventional colonial mediums such as text and analogue photography. The short film uses the technology to time travel, showing fictive histories and fictive futures from 1955 to 2055.

Musampizya (2024)

Banji Chona

Collaging visual poetry.

Musampizya is a body of work which exists as part of Healing The Dam(ned) a collaborative research project that begun in the latter part of 2023. It seeks to explore the impact that the Kariba Dam, an immense infrastructural scar of the colonial era, has had on the Indigenous baTonga communities in the middle-Zambezi Valley. This work investigates how the language of conservation and ecology is inextricably linked to colonial projects thus negating indigenous laws of environmental preservation. It also explores the sociocultural fractures initiated by the separation of the Batonga across present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. The main objective is to facilitate the reconstitution of the relationship between baTonga and the land in the contemporary context. Within the context of this projects, Artificial Intelligence, has been (re)coded as Ancestral Intelligence using the frameworks of Radical Zambezian Reimaginings. A methodology which accepts and prioritises fictive realities as being a necessary component in the healing of critical gaps in history, especially those of marginalised and silenced people and communities. Ancestral Intelligence (AI) is the tool first used in the development of Musampizya, a series of images which have been generated or rendered in the absence of images (free of colonial violence) of baTonga at the site of the dam, and in the surrounding woodlands. The series of rendered portraits and self-portraits, uses digital technology to challenge the way in which the history of places like Zambia, have been told by Western Historians and Researchers using conventional colonial mediums such as text and analogue photography.

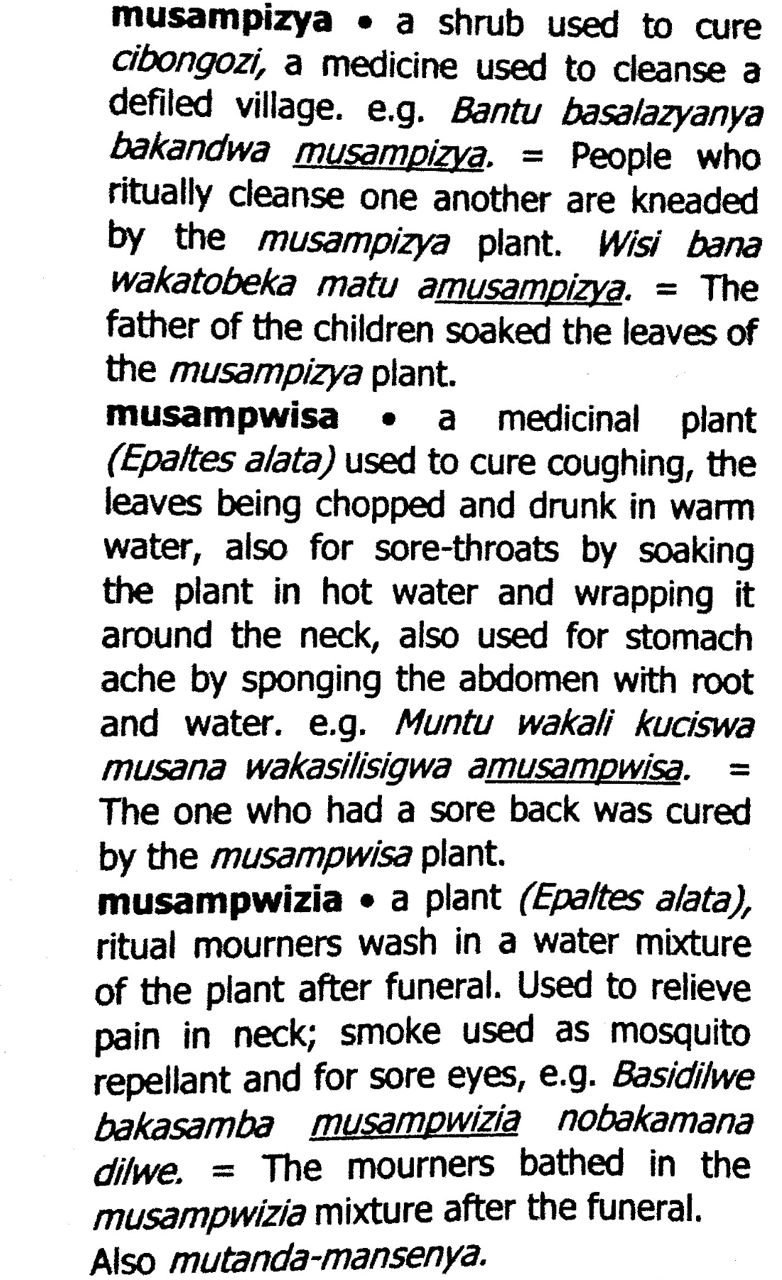

The name of this piece is borrowed from a shrub

that grows in areas in which baTonga lived and

live. It is a plant that served in various functions in

the world view of baTonga as both a cleansing

herb and a medicinal herb. I Imagine the spirit of

this (digitally alchemised) ancestor,

Namusampizya still roaming around the Gwembe

Valley looking for (and finding) all the sweet

smelling shrubs like epaltes alata to cleanse the

soil and homes of her Mukowa (future kin.) The

background is layered with a digitized image of

musila (red ochre) on canvas, a piece that’s been

hanging on my walls since I begun experimenting

with making natural paints.

Character stories

Character Stories is driven by the visceral need to attribute and reconstitute the instrinsic, non-exploitable value of baTonga women. It also exists as a direct challenge to the normative visual conceptions and projections of baTonga women found in the mainstream archive. baTonga women, in contemporary and historic visual culture, are often presesented as products, subjects or objects which exist as part of largely asymmetrical visual corpus mostly cemented by the western schools of Anthropology/Ethnography. Schools of thought whose foundational theories (and legitimacy in many ways) relied on the camera’s ability to capture curated scenes which corroborated the pre-conceived and often violent hypotheses of their carriers.

A number of photographs or videos of baTonga women which exist in the archive, mostly in public museums or private galleries in the occident, are often subtitled with the text “photograph of an unknown woman” and are devoid of any further data which alludes to the very core or centre of the photograph. This approach, renders baTonga women appedages of oppressive histories and narratives as opposed to autonomous agents of free will.

Character Stories challenges this gap in the documentation of dignified existences of baTonga people by virtue being written as people with recognizable and traceable names, extensive stories, timelines, families, hobbies etc.

Namusampizya is the name which has been given to the digitally alchemised ancestor shown in the series of images. She was named by her great-grandmother Luba who was a Sikatongo (earth priestess) and thus an oracle of sorts. Tonga naming traditions children either inherit ancestral names or are given names which reflect the charcter of the child or will reflect their charcater later on in life. Namusampizya translates as “mother of musampizya” a reference to her future fixation with sweet smelling shrubs such as epaltes alata and her work as an indigenous “botanist”.

eplaltes alata

She was born in approximately 1904 in a small village which was erased from the maps and the memory of people in the Gwembe Valley after the 1958 flooding of Kariba. In her teen years, she saw an apparition of her grandmother which asked her to spend twelve uninterrupted hours meditating underneath a Musikili tree. She listened. After feeling a connection like never before, Namusampizya dedicated her life to translating the language of plants into ciTonga through making oils and perfumes which she traded throughout the Gwembe Valley and into the Plateau in areas like Nampeyo and Haanjalika.

below: imagined footage of her home which was submerged underneath the raging flood of the Zambezi in 1958, a result of the Kariba being built on sacred waters.

SOURCE: REINDIGENISING FOOD FUTURE, SHORT FILM